I built a battery box out of a case from Harbor Freight. I had seen a similar box sold by Powerwerx for $259.99. Given the availability of these boxes at a much lower price ($34.99) and the cost of the parts involved ($140.78, with a bigger battery), I thought I’d be better off building a box at a reduced cost (~$176). I would also have the advantage of adding more PowerPole connectors instead of a cigarette lighter socket. If I ever need to plug into such a socket, I have a PowerPole to cigarette lighter socket adaptor that I made from spare parts.

While I did not compute labor costs in the box construction, I included all the parts (except the wiring, which I had lying around the shack). I find building little things like this relaxing. So, the labor costs aren’t really an issue for me. I didn’t even time how long it took me. If you find this laborious, You may want to just buy a box from Powerwerx.

Box Construction

To build this box, I had to drill 3 holes in the side that were big enough for the panel mounts. The three panel mounts I decided to include were a combination USB A/USB C/Voltmeter, and two mounts that house two PowerPole connections each for a total of 4 PowerPole connections.

I figured I could run a radio, an antenna tuner, and a light, which would use up three PowerPole plugs. I could use the fourth plug to simultaneously charge the battery if I’m somewhere with access to electricity or if I want to use a portable solar panel.

To drill these holes, I found that a stepped drill bit helped me select the right-sized hole for the size of the panel mounts. While not all panel mounts require the same size hole, they’re similar. This bit will help you step your way toward the right size so that the threads fit through but not the collar of the panel mount.

Once the holes are drilled, take the nut off the panel mount, slide the mount through the hole, and tighten the nut back on the panel mount until the collar of the panel mount is secure against the side of the box.

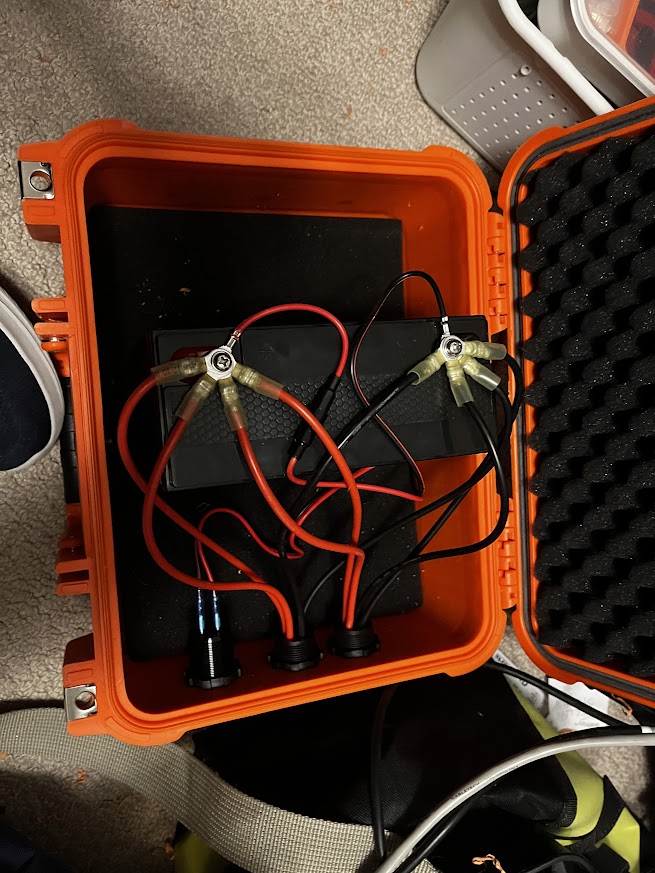

Wiring

Wiring is fairly simple. The USB charger comes with its own wire that has a ring on one end for the battery terminal and clips that fit into the back of the panel mount. It’s important to make sure that you get the polarity correct. A ‘+’ for positive (the red wire) and a ‘-‘ for negative (the black wire) is etched in the plastic. If you have trouble seeing them, a flashlight from a cellphone helps a lot.

When it comes to the PowerPoles, you have to be a little more attentive.

Make sure you use the right gauge of wire for the power you want to pull. I probably overdid it with 10 AWG wires, which kept me from putting multiple wires in a ring connector. With four think ring connectors, I barely got the battery screws to hold them down. However, I wanted to be able to pull enough amps to run my 100W radio and didn’t want to worry about which PowerPoles could handle which current. Having the 10 AWG wires on all of them makes that possible.

It is a best practice to use red for positive and black for negative. Doing so will make it less likely that you will attach the wires to the battery incorrectly.

Make sure that the wires are long enough to reach from the battery terminals to the PowerPoles. Put the rings on one wire end and PowerPole inserts on the other. Place the inserts into the PowerPole housings. Then, attach the rings to the terminals of the battery. Red to the positive screw and black to the negative screw.

Preventing Rattling

Once this is done, you’ll want to secure the battery. This step will keep the battery from rattling around when carrying the box by its handle. Fortunately, the box came with a bunch of foam rubber that can easily be separated to match the shape of whatever is being stored in the box. Carefully tear the rubber (along the perforations) to match the large area between the battery and the panel mounts. Then, use the scraps to fill in the area between the battery and the front of the case.

Testing the Battery

At this point, you’re ready to test the battery.

A button on the USB panel turns on the connectors and the voltmeter. Press the button and verify that the battery is charged. The full charge will be somewhere around 13.8V. If the voltmeter doesn’t show anything, the wiring polarity is likely incorrect. The battery probably needs to be charged (see below) if the voltage is too low.

Plug a USB cable into each port and verify that it charges your phone. This is probably what you’ll use it for. In my case, I use it to power a Raspberry Pi. If you want to do this, you’ll need a USB C port labeled PD.

Once the USB system works correctly, check the polarity of the PowerPole ports with a voltmeter. If the voltage is negative with the red lead connected to the red side and the black lead connected to the black side, you’ve wired it backward. If they are all positive, plug a device into each port and verify it has power. If so, you’re good to go.

Charging the Battery

To charge the battery, simply hook a charger to one of the PowerPole ports. I use NOCO chargers. I take the adaptor that comes with the charger and convert it PowerPoles to make this easier. For a battery this size, I use the 1 amp model. Be sure to set the charger’s battery type to the type of battery you put in the box. I use LiFePO4 batteries, so I set the charger to 12V Lithium.

Parts List

Here are the parts other than wires and connectors that I purchased to build this box.

You must be logged in to post a comment.